Differential form

In the mathematical fields of differential geometry and tensor calculus, differential forms are an approach to multivariable calculus that is independent of coordinates. Differential forms provide a more sophisticated definition for integrands in calculus. For instance, ƒ(x) dx is a 1-form that can be integrated over an interval [a,b] in the domain of ƒ

and similarly ƒ(x,y,z) dx∧dy + g(x,y,z) dx∧dz + h(x,y,z) dy∧dz is a 2-form that has a surface integral over any oriented surface S in the domain of g

Likewise, a 3-form ƒ(x, y, z) dx∧dy∧dz represents something that can be integrated over a region of space. The modern notion of differential forms was pioneered by Élie Cartan, and has many applications, especially in geometry, topology and physics.

The algebra of differential forms is organized in a way that naturally reflects the orientation of the domain of integration. There is an operation d on differential forms known as the exterior derivative that, when acting on a k-form produces a (k+1)-form. This operation extends the differential of a function, and the divergence and the curl of a vector field in an appropriate sense that makes the fundamental theorem of calculus, the divergence theorem, Green's theorem, and Stokes' theorem special cases of the same general result, known in this context also as Stokes' theorem. In a deeper way, this theorem relates the topology of the domain of integration to the structure of the differential forms themselves; the precise connection is known as De Rham's theorem.

The general setting for the study of differential forms is on a differentiable manifold. Differential 1-forms are naturally dual to vector fields on a manifold, and the pairing between vector fields and 1-forms is extended to arbitrary differential forms by the interior product. The algebra of differential forms along with the exterior derivative defined on it is preserved by the pullback under smooth functions between two manifolds. This feature allows geometrically invariant information to be moved from one space to another via the pullback, provided the information is expressed in terms of differential forms. As a particular example, the change of variables formula for integration becomes a simple statement that an integral is preserved under pullback.

Contents |

Concept

Differential forms provide an approach to multivariable calculus that is independent of coordinates.

Let U be an open set in Rn. A differential 0-form ("zero form") is defined to be a smooth function f on U. If v is any vector in Rn, then f has a directional derivative ∂v f, which is another function on U whose value at a point p ∈ U is the rate of change (at p) of f in the v direction:

(This notion can be extended to the case that v is a vector field on U by evaluating v at the point p in the definition.)

In particular, if v = ej is the jth coordinate vector then ∂vf is the partial derivative of f with respect to the jth coordinate function, i.e., ∂f / ∂xj, where x1, x2, ... xn are the coordinate functions on U. By their very definition, partial derivatives depend upon the choice of coordinates: if new coordinates y1, y2, ... yn are introduced, then

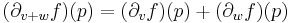

The first idea leading to differential forms is the observation that ∂v f (p) is a linear function of v:

for any vectors v, w and any real number c. This linear map from Rn to R is denoted dfp and called the derivative of f at p. Thus dfp(v) = ∂v f (p). The object df can be viewed as a function on U, whose value at p is not a real number, but the linear map dfp. This is just the usual Fréchet derivative — an example of a differential 1-form.

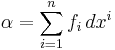

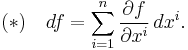

Since any vector v is a linear combination ∑ vjej of its components, df is uniquely determined by dfp(ej) for each j and each p∈U, which are just the partial derivatives of f on U. Thus df provides a way of encoding the partial derivatives of f. It can be decoded by noticing that the coordinates x1, x2,... xn are themselves functions on U, and so define differential 1-forms dx1, dx2, ..., dxn. Since ∂xi / ∂xj = δij, the Kronecker delta function, it follows that

The meaning of this expression is given by evaluating both sides at an arbitrary point p: on the right hand side, the sum is defined "pointwise", so that

Applying both sides to ej, the result on each side is the jth partial derivative of f at p. Since p and j were arbitrary, this proves the formula (*).

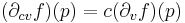

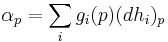

More generally, for any smooth functions gi and hi on U, we define the differential 1-form α = ∑i gi dhi pointwise by

for each p ∈ U. Any differential 1-form arises this way, and by using (*) it follows that any differential 1-form α on U may be expressed in coordinates as

for some smooth functions fi on U.

The second idea leading to differential forms arises from the following question: given a differential 1-form α on U, when does there exist a function f on U such that α = df? The above expansion reduces this question to the search for a function f whose partial derivatives ∂f / ∂xi are equal to n given functions fi. For n>1, such a function does not always exist: any smooth function f satisfies

so it will be impossible to find such an f unless

for all i and j.

The skew-symmetry of the left hand side in i and j suggests introducing an antisymmetric product  on differential 1-forms, the wedge product, so that these equations can be combined into a single condition

on differential 1-forms, the wedge product, so that these equations can be combined into a single condition

where

This is an example of a differential 2-form: the exterior derivative dα of α= ∑j=1n fj dxj is given by

To summarize: dα = 0 is a necessary condition for the existence of a function f with α = df.

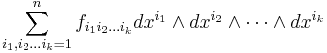

Differential 0-forms, 1-forms, and 2-forms are special cases of differential forms. For each k, there is a space of differential k-forms, which can be expressed in terms of the coordinates as

for a collection of functions fi1i2 ... ik. (Of course, as assumed below, one can restrict the sum to the case

Differential forms can be multiplied together using the wedge product, and for any differential k-form α, there is a differential (k + 1)-form dα called the exterior derivative of α.

Differential forms, the wedge product and the exterior derivative are independent of a choice of coordinates. Consequently they may be defined on any smooth manifold M. One way to do this is cover M with coordinate charts and define a differential k-form on M to be a family of differential k-forms on each chart which agree on the overlaps. However, there are more intrinsic definitions which make the independence of coordinates manifest.

Intrinsic definitions

Let M be a smooth manifold. A differential form of degree k is a smooth section of the kth exterior power of the cotangent bundle of M. At any point p∈M, a k-form β defines an alternating multilinear map

(with k factors of TpM in the product), where TpM is the tangent space to M at p. Equivalently, β is a totally antisymmetric covariant tensor field of rank k.

The set of all differential k-forms on a manifold M is a vector space, often denoted Ωk(M).

For example, a differential 1-form α assigns to each point p∈M a linear functional αp on TpM. In the presence of an inner product on TpM (induced by a Riemannian metric on M), αp may be represented as the inner product with a tangent vector Xp. Differential 1-forms are sometimes called covariant vector fields, covector fields, or "dual vector fields", particularly within physics.

Operations

There are several operations on differential forms: the wedge product of two differential forms, the exterior derivative of a single differential form, the interior product of a differential form and a vector field, and the Lie derivative of a differential form with respect to a vector field.

Wedge product

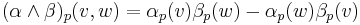

The wedge product of a k-form α and an l-form β is a (k + l)-form denoted αΛβ. For example, if k = l = 1, then αΛβ is the 2-form whose value at a point p is the alternating bilinear form defined by

for v, w ∈ TpM. (In an alternative convention, the right hand side is divided by two in this formula.)

The wedge product is bilinear: for instance, if α, β, and γ are any differential forms, then

It is skew commutative (also known as graded commutative), meaning that it satisfies a variant of anticommutativity that depends on the degrees of the forms: if α is a k-form and β is an l-form, then

Riemannian manifold

On a Riemannian manifold, or more generally a pseudo-Riemannian manifold, vector fields and covector field can be identified (the metric is a fiber-wise isomorphism of the tangent space and the cotangent space), and additional operations can thus be defined, such as the Hodge star operator  and codifferential

and codifferential  (degree

(degree  ) which is adjoint to the exterior differential d.

) which is adjoint to the exterior differential d.

Vector field structures

On a pseudo-Riemannian manifold, 1-forms can be identified with vector fields; vector fields have additional distinct algebraic structures, which are listed here for context and to avoid confusion.

Firstly, each tangent space (and thus vector fields) generate a Clifford algebra. The product of two vectors in a Clifford algebra differs from the exterior product of k-vectors (dual to the exterior product of k-forms): In a Clifford algebra the square of a vector is computed by evaluating a quadratic form, whereas the exterior product of two k-vectors is always 0. Clifford algebras are a non-anti-commutative ("quantum") deformation of the exterior algebra. This structure is used in geometric algebra.

Another alternative is to consider vector fields as derivations, and consider the (noncommutative) algebra of differential operators they generate, which is the Weyl algebra, and is a noncommutative ("quantum") deformation of the symmetric algebra in the vector fields.

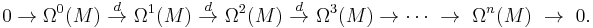

Exterior differential complex

One important property of the exterior derivative is that d2 = 0. This means that the exterior derivative defines a cochain complex:

By the Poincaré lemma, this complex is locally exact except at Ω0(M). Its cohomology is the de Rham cohomology of M.

Pullback

One of the main reasons the cotangent bundle rather than the tangent bundle is used in the construction of the exterior complex is that differential forms are capable of being pulled back by smooth maps, while vector fields cannot be pushed forward by smooth maps unless the map is, say, a diffeomorphism. The existence of pullback homomorphisms in de Rham cohomology depends on the pullback of differential forms.

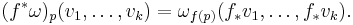

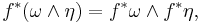

Differential forms can be moved from one manifold to another using a smooth map. If f : M → N is smooth and ω is a smooth k-form on N, then there is a differential form f*ω on M, called the pullback of ω, which captures the behavior of ω as seen relative to f.

To define the pullback, recall that the differential of f is a map f* : TM → TN. Fix a differential k-form ω on N. For a point p of M and tangent vectors v1, ..., vk to M at p, the pullback of ω is defined by the formula

More abstractly, if ω is viewed as a section of the cotangent bundle T*N of N, then f*ω is the section of T*M defined as the composite map

Pullback respects all of the basic operations on forms:

The pullback of a form can also be written in coordinates. Assume that x1, ..., xm are coordinates on M, that y1, ..., yn are coordinates on N, and that these coordinate systems are related by the formulas yi = fi(x1, ..., xm) for all i. Then, locally on N, ω can be written as

where, for each choice of i1, ..., ik,  is a real-valued function of y1, ..., yn. Using the linearity of pullback and its compatibility with wedge product, the pullback of ω has the formula

is a real-valued function of y1, ..., yn. Using the linearity of pullback and its compatibility with wedge product, the pullback of ω has the formula

Each exterior derivative dfi can be expanded in terms of dx1, ..., dxm. The resulting k-form can be written using Jacobian matrices:

Integration

Differential forms of degree k are integrated over k dimensional chains. If k = 0, this is just evaluation of functions at points. Other values of k = 1, 2, 3, ... correspond to line integrals, surface integrals, volume integrals etc. Simply, a chain parametrizes a domain of integration as a collection of cells (images cubes or other domains D) that are patched together; to integrate, one pulls back the form on each cell of the chain to a form on the cube (or other domain) and integrates there, which is just integration of a function on  as the pulled back form is simply a multiple of the volume form

as the pulled back form is simply a multiple of the volume form  For example, given a path

For example, given a path ![\gamma(t) \colon [0,1] \to \mathbf{R}^2,](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/34b3edc063241e4f4a091f3f403e7ee6.png) integrating a form on the path is simply pulling back the form to a function on

integrating a form on the path is simply pulling back the form to a function on ![[0,1]](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/ccfcd347d0bf65dc77afe01a3306a96b.png) (properly, to a form

(properly, to a form  ) and integrating the function on the interval.

) and integrating the function on the interval.

Let

be a differential form and S a differentiable k-manifold over which we wish to integrate, where S has the parameterization

for u in the parameter domain D. Then (Rudin 1976) defines the integral of the differential form over S as

where

is the determinant of the Jacobian. The Jacobian exists because S is differentiable.

More generally, a  -form can be integrated over an

-form can be integrated over an  -dimensional submanifold, for

-dimensional submanifold, for  , to obtain a

, to obtain a  -form. This comes up, for example, in defining the pushforward of a differential form by a smooth map

-form. This comes up, for example, in defining the pushforward of a differential form by a smooth map  by attempting to integrate over the fibers of

by attempting to integrate over the fibers of  .

.

Stokes' theorem

The fundamental relationship between the exterior derivative and integration is given by the general Stokes theorem: If  is an n−1-form with compact support on M and ∂M denotes the boundary of M with its induced orientation, then

is an n−1-form with compact support on M and ∂M denotes the boundary of M with its induced orientation, then

A key consequence of this is that "the integral of a closed form over homologous chains is equal": if  is a closed k-form and M and N are k-chains that are homologous (such that M-N is the boundary of a (k+1)-chain W), then

is a closed k-form and M and N are k-chains that are homologous (such that M-N is the boundary of a (k+1)-chain W), then  since the difference is the integral

since the difference is the integral

For example, if  is the derivative of a potential function on the plane or

is the derivative of a potential function on the plane or  then the integral of

then the integral of  over a path from a to b does not depend on the choice of path (the integral is

over a path from a to b does not depend on the choice of path (the integral is  ), since different paths with given endpoints are homotopic, hence homologous (a weaker condition). This case is called the gradient theorem, and generalizes the fundamental theorem of calculus). This path independence is very useful in contour integration.

), since different paths with given endpoints are homotopic, hence homologous (a weaker condition). This case is called the gradient theorem, and generalizes the fundamental theorem of calculus). This path independence is very useful in contour integration.

This theorem also underlies the duality between de Rham cohomology and the homology of chains.

Relation with measures

On a general differentiable manifold (without additional structure), differential forms cannot be integrated over subsets of the manifold; this distinction is key to the distinction between differential forms, which are integrated over chains, and measures, which are integrated over subsets. The simplest example is attempting to integrate the 1-form dx over the interval [0,1]. Assuming the usual distance (and thus measure) on the real line, this integral is either 1 or −1, depending on orientation:  while

while  By contrast, the integral of the measure dx on the interval is unambiguously 1 (formally, the integral of the constant function 1 with respect to this measure is 1). Similarly, under a change of coordinates a differential n-form changes by the Jacobian determinant J, while a measure changes by the absolute value of the Jacobian determinant,

By contrast, the integral of the measure dx on the interval is unambiguously 1 (formally, the integral of the constant function 1 with respect to this measure is 1). Similarly, under a change of coordinates a differential n-form changes by the Jacobian determinant J, while a measure changes by the absolute value of the Jacobian determinant,  which further reflects the issue of orientation. For example, under the map

which further reflects the issue of orientation. For example, under the map  on the line, the differential form

on the line, the differential form  pulls back to

pulls back to  orientation has reversed; while the Lebesgue measure, also denoted

orientation has reversed; while the Lebesgue measure, also denoted  pulls back to

pulls back to  it does not change.

it does not change.

In the presence of the additional data of an orientation, it is possible to integrate n-forms (top-dimensional forms) over the entire manifold or over compact subsets; integration over the entire manifold corresponds to integrating the form over the fundamental class of the manifold, ![[M].](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/80500338d252bb0298eea3b39024c104.png) Formally, in the presence of an orientation, one may identify n-forms with densities on a manifold; densities in turn define a measure, and thus can be integrated (Folland 1999, Section 11.4, pp. 361–362).

Formally, in the presence of an orientation, one may identify n-forms with densities on a manifold; densities in turn define a measure, and thus can be integrated (Folland 1999, Section 11.4, pp. 361–362).

On an orientable but not oriented manifold, there are two choices of orientation; either choice allows one to integrate n-forms over compact subsets, with the two choices differing by a sign. On non-orientable manifold, n-forms and densities cannot be identified - notably, any top-dimensional form must vanish (there are no volume forms on non-orientable manifolds), but there are non-vanishing densities - thus while one can integrate densities over compact subsets, one cannot integrate n-forms.

There is in general no meaningful way to integrate k-forms over subsets for  because there is no consistent way to orient k-dimensional subsets; geometrically, a k-dimensional subset can be turned around in place, reversing any orientation but yielding the same subset. Compare the Gram determinant of a set of k vectors in an n-dimensional space, which, unlike the determinant of n vectors, is always positive, corresponding to a squared number.

because there is no consistent way to orient k-dimensional subsets; geometrically, a k-dimensional subset can be turned around in place, reversing any orientation but yielding the same subset. Compare the Gram determinant of a set of k vectors in an n-dimensional space, which, unlike the determinant of n vectors, is always positive, corresponding to a squared number.

On a Riemannian manifold, one may define a k-dimensional Hausdorff measure for any k (integer or real), which may be integrated over k-dimensional subsets of the manifold. A function times this Hausdorff measure can then be integrated over k-dimensional subsets, providing a measure-theoretic analog to integration of k-forms. The n-dimensional Hausdorff measure yields a density, as above.

Applications in physics

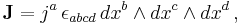

Differential forms arise in some important physical contexts. For example, in Maxwell's theory of electromagnetism, the Faraday 2-form, or electromagnetic field strength, is

where the  are formed from the electromagnetic fields

are formed from the electromagnetic fields  and

and  , e.g.

, e.g.

, or equivalent definitions.

, or equivalent definitions.

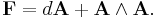

This form is a special case of the curvature form on the U(1) principal fiber bundle on which both electromagnetism and general gauge theories may be described. The connection form for the principal bundle is the vector potential, typically denoted by A, when represented in some gauge. One then has

The current 3-form is

where  are the four components of the current-density. (Here it is a matter of convention, to write

are the four components of the current-density. (Here it is a matter of convention, to write  instead of

instead of  i.e. to use capital letters, and to write

i.e. to use capital letters, and to write  instead of

instead of  . However, it should be noted that the vector rsp. tensor components and the above-mentioned forms have different physical dimensions. Moreover, one should remember that by decision of an international commission of the IUPAP, the magnetic polarization vector is called

. However, it should be noted that the vector rsp. tensor components and the above-mentioned forms have different physical dimensions. Moreover, one should remember that by decision of an international commission of the IUPAP, the magnetic polarization vector is called  since several decades, and by some publishers

since several decades, and by some publishers  i.e. the same name is used for totally different quantities.)

i.e. the same name is used for totally different quantities.)

Using the above-mentioned definitions, Maxwell's equations can be written very compactly in geometrized units as

where  denotes the Hodge star operator. Similar considerations describe the geometry of gauge theories in general.

denotes the Hodge star operator. Similar considerations describe the geometry of gauge theories in general.

The 2-form  which is dual to the Faraday form, is also called Maxwell 2-form.

which is dual to the Faraday form, is also called Maxwell 2-form.

Electromagnetism is an example of a U(1) gauge theory. Here U(1) is a Lie group, the one-dimensional unitary group, which is in particular abelian. There are gauge theories, such as Yang-Mills theory, in which the group is not abelian. In that case, one gets relations which are similar to those described here. The analog of the field F in such theories is the curvature form of the connection, which is represented in a gauge by a Lie algebra-valued one-form A. The field F is then defined by

In the abelian case, such as electromagnetism,  , but this does not hold in general. Likewise the field equations are modified by additional terms involving wedge products of A and F, owing to the structure equations of the gauge group.

, but this does not hold in general. Likewise the field equations are modified by additional terms involving wedge products of A and F, owing to the structure equations of the gauge group.

Applications in geometric measure theory

Numerous minimality results for complex analytic manifolds are based on the Wirtinger inequality for 2-forms. A succinct proof may be found in Herbert Federer's classic text Geometric Measure Theory. The Wirtinger inequality is also a key ingredient in Gromov's inequality for complex projective space in systolic geometry.

See also

References

- Bachman, David (2006), A Geometric Approach to Differential Forms, Birkhauser, ISBN 978-0-8176-4499-4

- Bachman, David (2003), A Geometric Approach to Differential Forms, arXiv.org

- Folland, Gerald B. (1999), Real Analysis: Modern Techniques and Their Applications (Second ed.), ISBN 978-0-47131716-6, provides a brief discussion of integration on manifolds from the point of view of measure theory in the last section.

- Flanders, Harley (1989), Differential forms with applications to the physical sciences, Mineola, NY: Dover Publications, ISBN 0-486-66169-5

- Fleming, Wendell H. (1965), "Chapter 6: Exterior algebra and differential calculus", Functions of Several Variables, Addison-Wesley, pp. 205–238. This textbook in multivariate calculus introduces the exterior algebra of differential forms at the college calculus level.

- Morita, Shigeyuki (2001), Geometry of Differential Forms, AMS, ISBN 0-8218-1045-6

- Rudin, Walter (1976), Principles of Mathematical Analysis, New York: McGraw-Hill, ISBN 0-07-054235-X

- Spivak, Michael (1965), Calculus on Manifolds, Menlo Park, CA: W. A. Benjamin, ISBN 0-8053-9021-9, standard introductory text.

- Tu, Loring W. (2008), An Introduction to Manifolds, Springer, ISBN 978-0-387-48098-5

- Zorich, Vladimir A. (2004), Mathematical Analysis II, Springer, ISBN 3-540-40633-6

External links

- Weisstein, Eric W., "Differential form" from MathWorld.

- Sjamaar, Reyer (2006), Manifolds and differential forms lecture notes, http://www.math.cornell.edu/~sjamaar/classes/3210/notes.html, a course taught at Cornell University.

- Bachman, David (2003), A Geometric Approach to Differential Forms, arXiv:math/0306194, an undergraduate text].